According to tribal legend, the Southern Ute Indians have lived in the mountains of Colorado since the beginning of time. They hunted, fished, and foraged for food in a land of plenty for centuries. They were already expert hunters when Spanish-speaking explorers arrived in the 16th Century. With the help of guns and horses the Utes became even more fearsome hunters and warriors.

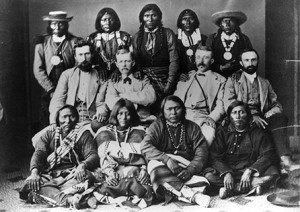

The Utes’ ancestral land was high in the Rocky Mountains. As Anglo-American settlers began to pour into Colorado early in the 19th Century, the Utes were insulated from their encroachment by a buffer of plains tribes and the rugged peaks of Colorado’s Front Range. In 1863, Colorado Governor John Evans signed a treaty with nine Ute chiefs, including Chief Ouray, giving all land east of the continental divide to the United States and preserving all land west of the divide for the Utes. By 1868, however, the white people of Colorado decided that they had given too much land to the Utes. Ouray and nine other chiefs were invited to Washington to negotiate a new treaty.

In the end, Ouray signed a treaty that allowed his people to keep 16 million acres. This was still a substantial sacrifice to the United States, but was much less than what the white negotiators had hoped to obtain. Ouray also had language added to the treaty which stated that no unauthorized white man would “ever be permitted to pass over, reside in or settle upon” the land allotted to the Utes.

This clause did little to keep homesteaders and prospectors from trespassing on Ute land. Among them was Frederick Pitkin who had made a fortune in mining and was a powerful advocate in Denver for the state’s acquisition of the San Juan Mountains, amounting to ¼ of what remained of Ute land. Pitkin and others eventually convinced the Utes that if they did not sell, the land would simply be taken. In the end, the Utes agreed to sell for $25,000.

In 1878, E.H. Danforth, a relatively friendly agent from the Bureau of Indian Affairs, was replaced by the paternalistic Nathan Meeker. Meeker was committed to bringing the Utes out of the “savage state” and into the “enlightened, scientific, and religious stage.”

A series of insensitive acts on Meeker’s part helped to alienate the Utes over a period of several years. Eventually, Meeker began fabricating reports that a band of Utes was tormenting nearby settlers. By this time, Frederick Pitkin, no friend of the Utes, was Governor of Colorado and tales of savagery on the part of Indians meshed well with his opinion of Native Americans.

Finally, Meeker wrote to Pitkin that he was in fear for his life. Two-hundred soldiers were sent to bolster Meeker’s post. The arrival of the troops concerned and frightened the peaceful Utes and some young warriors began to prepare for a confrontation. Cool-headed elder chiefs rode out under a flag of truce to meet the column of soldiers and came to an agreement with their commander, Major Thornburgh, that he would stop his troops outside Ute territory to avoid conflict.

When Thornburgh crossed into Ute lands however, he did not stop as he had said he would. This decision led his troops directly into the path of a group of angry, young Ute braves. A skirmish ensued. It was not clear who fired the first shot. When the Utes near the agency heard that their brothers had been attacked, they shot all the white men at the agency and absconded with three female prisoners.

When tales of the conflict reached Denver, Governor Pitkin and his allies gladly exaggerated stories of Ute brutality. In 1880, the ailing Chief Ouray returned to Washington to negotiate a new treaty, but he was not the shrewd negotiator he had once been. He did not live to see the government force his people onto a reservation in Utah a year later, carved out of land the Mormon settlers did not want.

Pete Wadden formerly worked at Walking Mountains Science Center and is currently the Watershed Education Coordinator at the Town of Vail.